Takehiko Inoue’s Real is a manga about loss, disability, and identity. If you’ve ever had to start over, this raw, powerful story might hit home.

Real, a seinen manga by Takehiko Inoue (Slam Dunk, Vagabond) is the best manga that you’ve never read. You probably have zero interest in it. It’s not surprising, because I had no interest in it, either. A manga about wheelchair basketball sounds boring, or depressing, or preachy. Why would anyone want to read that?

But, like all good stories, Real isn’t about what it’s about. It’s actually about identity, and perseverance, and rebuilding yourself when the person you thought you were is no longer the person you are allowed to be. It’s about continuing to push forward in chasing a passion, even if life has brutally told you “no”.

Real is also about forgiveness, and whether you can give it to others, and whether you deserve it yourself. It’s about attempting to right wrongs, and learning to accept when you can’t. It’s about making lemonade when life hands you lemons.. or, at least trying to accept that lemons can be beautiful.

Three characters, one theme

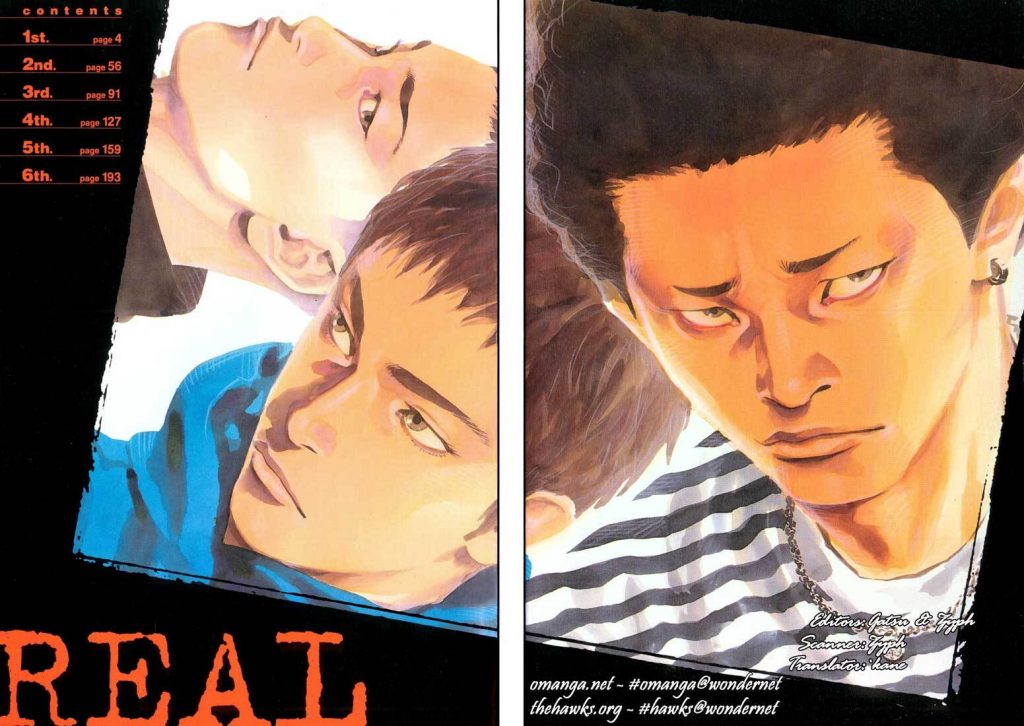

The story focuses on three main characters. Togawa, who plays wheelchair basketball, Nomiya, a dropout high school basketball player, and Takahashi, the alpha male new captain of Nomiya’s school team.

Togawa, a former national-level sprinter, is one of the most compelling disabled manga characters I’ve ever read. At the beginning of Real, he is the furthest along on his journey of change, having already done a lot of the hard work of processing the grief and loss of his limb. This is largely due to coming to terms with his poor relationship with his father, and meeting a mentor who introduces him to wheelchair basketball. Togawa has largely reinvented himself, and is passionate about his friends and his team.

Nomiya is far behind Togawa, but he’s trying. He is passionate about basketball, but drops out of high school and quits his team after causing a motorcycle accident that cost his passenger, Natsumi, the use of her legs. He is filled with survivor’s guilt and is determined to make things right with Natsumi, even though it’s impossible. The loss of basketball weighs on him heavily. You see, Japan isn’t like America. There aren’t basketball hoops on every school yard and playground. If you’re not on a team, it’s hard to play. And, equally important, Nomiya misses belonging to a team. He’s lost, but searching for a guiding compass.

Takahashi, by contrast, is the furthest behind, emotionally, on the path of reinvention. When the story starts he is popular, flashy, cocky. His entire identity is tied up in basketball. But not being good at basketball, or loving basketball.. he cares about being popular from basketball. That is, until he is hit by a truck, leading to him becoming a paraplegic. He has lost everything important to him, and he wallows in self pity, hatred, and anger. He has a lot of work to do before he can even begin to figure out: well, what’s next?

Inoue’s Real is about resilience and change

And that’s really what Real is about: What’s next?

I can’t run anymore. What’s next?

I can’t play basketball anymore. What’s next?

I can’t walk. What’s next?

I severely injured another person. What’s next?

It’s continually, thoughtfully and skillfully posing the question. Here’s your situation. You are no longer who you thought you were. So. What’s next? Are you going to give up? Or are you going to figure something else out. Are you going to keep pushing, or are you going to pivot? Those are the questions each of the 3 protagonists face, daily.

Do I even have value at all anymore?

Togawa has already changed dramatically from begrudged piano prodigy to champion sprinter to wheelchair basketball captain, but it’s never really over, is it? He faces challenges with his childhood best friend, with his team, with trying to join the national team, with his family. He has come far, but where is he going from here?

Nomiya is still trying to figure it out. He’s struggling, but trying. School is out. But what’s still possible for me? He tries a string of part time jobs, he helps coach Togawa’s team, he tries to support Natsumi, and he tries out for a Japanese pro basketball team even though everyone says it’s out of his reach.

Takahashi’s path is darker, and we follow him at its darkest. The questions posed to him are much more visceral. Do I just end it? Is it worth putting in months, years, of work, just so I can learn to pick myself up off the floor in case I fall out of my wheelchair? Do I even have value at all anymore?

If you’ve ever had to start over, or you’re still figuring out how to, this manga gets it.

It’s really hard to figure that out, though

Togawa and Nomiya’s struggles resonate deeply with me. Like both, I have lost the ability to play tennis, a sport that was a huge part of my life and identity, due to arthritis in both hips. While I very happily can still walk, running, jumping, and the other physical demands of tennis are just impossible. Tennis is gone for me, and it’s never coming back. That was genuinely devastating, and I’ve been grappling with it for years.

Also, similar to Nomiya, I’ve been struggling with the guilt of people I’ve hurt. One person in particular. Struggling with accepting the fact that that damage has been done, and it can never be undone. Any attempt to fix it will only cause more pain. So the only way forward, the right way forward, is to leave them alone. It’s a tough pill to swallow, but doing the right thing often is.

And so, I’ve been asking myself that same basic question. What’s next? I can’t play tennis anymore. What can I do? I can’t fix my relationships, but what can I do?

Leave things better than how you found them

I don’t have the answers, personally, but I’m still trying. I do know that I want to leave things better than how I found them, and make cool things, and encourage people’s passions and interests. That’s what 「gan·ba·re!」is. The “do your best” encouragement from one friend to another. The idea of being the best you you can be, at least for today, because honestly that’s all anybody can expect of themselves.

It’s difficult, and it’s painful, but it’s worth it. And like Togawa, Nomiya, and Takahashi, I’m trying.

So yeah, Inoue’s Real is worth reading

So. Read Real. But only if you like complex stories, characters with emotional depth, and well executed themes of growth, adaptation, and re-invention. Oh, and absolutely stunning artwork as well. If you’re hoping for exciting wheelchair basketball action, well. There’s some of that too. But it’s not the point.

Like all good stories, Real isn’t about what it’s about.